I hardly had time to finish breakfast this morning when suddenly a pickup truck with some 20some people crammed on board rolls up in front of my house.

Most of the passengers are from Hain; their clothes are much more ragged than usual and they all have hand hoes slung over the shoulder.

In the driver seat is Evans, RAAP’s director, who is sporting the biggest grin I’ve ever seen and screaming

“we’re going farming!”

I quickly grab a hat and hop on the back, somehow finding a place to sit among the mass of bodies (who are, incidentally, all laughing at the fact that the white guy is going to try to farm).

After exchanging greetings the conversation immediately goes to a level of Dagaare I can’t quite follow so I’m left to retreat into my head and admire the scenery as Evans blazes down the dirt road at a speed that can only be described as “unsafe.”

After a few kilometres (and several additional passengers) we turn off of the main road and head off into the bush.

The ride immediately gets a lot rougher; everyone in the back grabs onto someone across from them, creating an interesting yet effective web that prevents us all from being flung from the truck.

Occasionally I glance forward to see where we were going; I literally can’t see the ‘road’ that we’re driving along.

The path seems to be nothing more than a series of bushes and rocks that are slightly smaller and lower than those on either side of the trail.

I am a little uneasy about this, but no-one else seems to mind.

Eventually we reach our destination: a couple straw huts and a few dozen acres of maize and groundnuts.

We all jump off the back and join a few dozen more farmers who are already marching off towards the groundnut field.

The women stay back at the huts and begin preparing the massive amount of food and drink that will be needed in a couple hours.

Off to my right I notice a line of women heading towards the huts carrying massive containers of water on the head.

I’m told the stream they’re coming from is at least 3 kilometres away.

As seems to be the case with all Ghanaians, the farmers are invariably in a good mood throughout the walk.

Off to the left I can see another group making their way to the same farm.

Meanwhile many more farmers go shooting past us on either side, completely unfazed by the fact that they are riding over grass on rickety old bicycles that have no brakes.

Ahead one of the men starts a chant that I can only describe as a Dagaare alternative to the Seven Dwarfs’ favourite song.

We arrive at the field to see that fifty or so farmers have already started to weed.

Spread out over several acres, they look as if they are farming at random in all directions.

Every minute or so someone starts shouting a random half-song, which is only sometimes answered.

I could never quite make out what they were saying and for some reason I never bothered to ask.

Whatever it was, it seemed to keep everyone in good spirits, which I imagine was the point.

While we are walking to the far corner of the plot Evans explains to me that all this land is owned by a local man named Moses.

Several years ago Moses helped Evans’ family farm their land and so now he is trying to repay the favour; most of RAAP has come out to spend the day weeding.

All told, over 100 people from all the neighbouring villages have come together with the hope that together they can finish all of Moses’ thirty plus acres of land by the end of the day.

Upon reaching our section of land I discover that the farming is not as random as it first seemed; the entire process is coordinated by a few farmers who mark out “contracts” for which each farmer is responsible.

Once he is done his area the farmer is free to either help others or rest until everyone has finished their respective sections.

Not only does this ensure that everyone does a comparable amount of work, but it also makes many people work faster since they see it as a race to finish their contract before the farmer next to them does.

In less than an hour we finish up the first field, which looked to be just over three acres.

Everyone then fans out and works his way back towards the cooking hut, weeding anything that gets in his way.

Before noon hits we’re done another six or more acres, finishing all of the groundnut fields.

At this point I’m beginning to feel a little more than exhausted (everyone else seems just as energetic as when they started).

Much to my relief, I discover that we get a brief break before moving on to the maize fields.

As the women serve everyone drinks before lunch I’m reminded at just how well religions mix here.

The farmers divide into two groups, with the predominantly Christian group taking pito, the local alcoholic drink, and the predominantly Muslim group taking a mix of water and ground vegetables.

Everyone then reassembles and breaks into a series of smaller groups, where giant tubs of beans and rice are served and quickly devoured.

The meal ends at 1pm and all the Christian farmers relax for a few minutes while their Muslim counterparts begin their prayers.

Once the prayers finish everyone assembles again, throwing their hoes into the middle of the circle.

Several of the leaders then rearrange the hoes into three piles that represent the three different maize fields that we are to finish by the end of the day.

Though I spent years picking road hockey teams in a similar fashion, I’m baffled by the process because, unlike our hockey sticks with varying colours and brands, every one of the 100+ hoes is the same model of unpainted wood.

My questions and worries are met with laughs and stares; every farmer knows exactly which hoe is his and finds it without hesitation.

We break off and, for the first time, I am given my own contract.

Sort of.

I work as hard and fast as I can, but I can’t help but notice that my section is getting done a great deal slower than everyone else’s, despite the fact that the farmers around me often farm a little bit into my section.

This doesn’t come as a surprise, mind you, but it is rather frustrating since I am working at a furious pace and am becoming completely exhausted; a nice reminder that I can’t possibly understand (much less perform) the amount of physical labour the average villager has to do for their daily food.

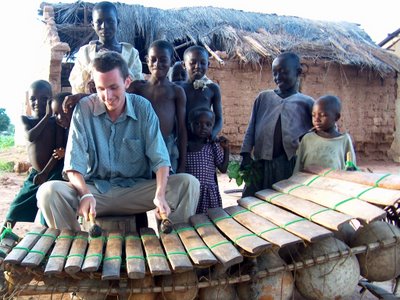

I should mention, if you haven’t already noticed in the photographs, that the day was overcast and very cool by

Ghana’s standards.

I am very, very grateful for this.

Though the clouds made my hat mostly useless, they saved me from the agony of working under a harsh equatorial sun.

(I should also point out that a dozen or so farmers were wearing toques for most of the day, which was more than a little amusing to me.)

By about 2:30 we finish up our maize field, only to find that another group, who had much rockier ground to work through, isn’t quite half done theirs.

We immediately rush over and help them complete the remainder of their field in an amazingly short period of time; a few acres can’t stand up to a hundred farmers who are determined to finish and go home.

As the last sections were being completed I walk over to Evans and Emmanuel, another RAAP employee, who were discussing their thoughts on the day.

As I was approaching I could overhear Emmanuel saying “the unity alone is enough to make me happy.”

I couldn’t agree more; there was a good natured, optimistic atmosphere that made the huge amount of work bearable.

The sense of community and camaraderie was almost overwhelming and never once faltered throughout the whole day.

Once our work finished everyone crammed onto trucks and bicycles and raced home to get cleaned up before the sun set.

(The bucket showers were certainly needed!)

After we washed we re-convened in the evening, where four goats were killed in our honour.

The village elders thanked us all for our work, and the day finished with a huge feast around a roaring fire, with plenty of songs, drinks and dances.

By the time I got home the moon was already high in the sky and my body felt like it was going to fall apart before I could drag it to its bed.

I made it, though, and as I crawled under my mosquito net I collapsed on the mattress and thanked my lucky stars that this was only a one day affair; I definitely don’t have enough strength left in me to do it all over again tomorrow.

Unfortunately, the other hundred some farmers aren’t so lucky.