Today I was able to go the field and experience more REFLECT community meetings.

So, as promised, here’s a proper entry about the most rich and beneficial experience of my placement thus far.

I woke up at 6:30am this morning and, after a quick refreshing bucket shower, was ready when Jude picked me up at 7am, relatively late in the morning by African standards.

After a brief stop at the office to gas up, we raced off on his motorbike down a dirt road that would have made an insurance agent cry.

Throughout the drive I can hear the kids screaming

“Nansaalah! Nansaalah! HowareYOU!!” as we passed.

Sometimes they even turn it into a song (with no appropriate pauses for you to respond)

“Nansaalah. How are you. We are fine. Thank you!” I can’t really do much else but smile and wave back as we continue down the road.

The adults are equally as friendly, though they don’t waste their energy shouting at a motorbike.

As we drive I can’t help but wonder (for the thousandth time) if everybody is only so friendly because I am white, or if they’re actually this friendly thanks to a culture that is inherently kinder than our own.

I think both factor in...

We arrived at the site to find 50 people already gathered, most of them women; the men had already left to farm and the women all stayed in town because in was Kaani’s market day (once every 6 days a town hosts a market, where all the surrounding community members come and sell their goods).

Before Jude and I had come to a stop Raphael, who was the other RAAP worker with us, had already started to lead the group in a big sing-along.

He starts with what looks to be the chief, and then one by one he works his way around the circle, with each person singing a couple lines and the entire group responding.

The lyrics are the same for each person, with the exception of the last line, which they seemed to make up for themselves (or at least I could hear no pattern to it).

As Raphael came around to me I sang the main part, which I had already been repeated enough to be memorized, and then quickly mumbled something at the end for the last line while shooting the crowd my best sheepish grin.

It worked; they had to stop the song while everyone ran around laughing, shouting, clapping and high-fiving me for my attempt.

I couldn’t help but grin—from the first community visit we did it was apparent that no village would let me simply stand off to the side and observe; and so there’s usually no choice but to throw yourself into the singing and dancing and try to get as many laughs as you can.

I’ve found that people accept your presence much faster if you goof around during the ‘fun time’ of the meeting, as goofing around is an inherent part of almost all social life here.

The fact is that the villages usually want to see the white guy sing/dance, and once you show them you’re able to have a good time they more easily accept your presence for the remainder of the meeting, allowing you to step off to the side and observe the meeting while being relatively unnoticed.

I found it interesting that, by the time the song and dance finished, over 100 people had gathered—all of those originally “too busy” to join the meeting suddenly wanted to join in the fun.

A very effective way to start off a meeting (I told you RAAP was good)!

As the meeting got underway I quickly scanned the crowd.

Most were traditionally dressed, but some had obviously Western clothing: ripped jeans, baseball caps, and t-shirts reading “Nike,” “Madonna,” “50 Cent” and, my favourite, “I Love My Attitude Problem." Scanning the crowd I realized that I had no idea how old most of the women in the crowd were; their faces were hardened by the sheer volume of hard work they did, sometimes making them seem decades older than they probably were.

(If there’s one thing I’ve learned so far, it’s that women here do at least 80% of the work and get 0% of the thanks/respect.)

After introductions finished I became almost completely lost, since I’m not exactly fluent in Dagaare.

In other meetings it was better for me, as the facilitators always used REFLECT tools which are easy to interpret and require little verbal explanation.

This meeting, however, was the first REFLECT meeting run in this community, so it was an introduction to the program, tools, and songs—with an emphasis on speech rather than symbols.

I had no choice but to sit back, relax, and watch the meeting progress; observing how people spoke and reacted to the speakers.

As I was sitting there I thought back to the first community visit we did, in which they created a “Health Calendar.”

The facilitators had drawn a grid in the sand and the community used random materials lying around to represent diseases, placing them in the seasons in which they were a problem.

The community members themselves decided what objects to use and what diseases they represented.

As each person stood to pick an item, they had to describe why they made their choice and how the object related to the disease.

Most of the items chosen held a very obvious link to the disease associated with them.

Except one; a gentleman picked up a hard quarter-shell of one of their local fruits and announced to the crowd that it represented malaria (to which several people snickered).

Even our NGO director could hardly keep a straight face when he asked what on earth an old piece of shell had to do with malaria.

The man’s response, however, silenced the crowd.

I found out later what he said:

“This shell, if left face up, will collect rainwater. This still pool of water can then breed mosquitoes. These mosquitoes, in turn, will bite us and give us malaria.”

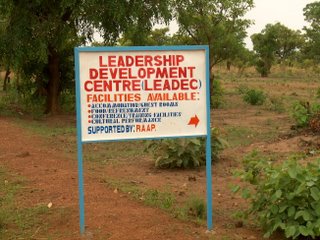

I should note here that ever since hearing this I’ve made a point of running around LEADEC emptying any and everything that could possibly collect water after each rainfall.

(The villagers aren’t the only ones learning during these meetings!)

Anyway, the Kaani meeting ended after almost two and a half hours.

Immediately a few kids came running up to me to shake hands and to invite me to join the football game that they were about to start.

I declined, saying we had to go.

After a very brief moment of sadness one of them kicked the ball towards the field and the rest of them went screamed on after it.

I turned to see that a couple women had been watching me; they smiled and waved.

I'm not quite sure how to end this so I'll take this opportunity to post my mailing address and phone number:

Bryn Ferris

C/O RAAP

PO Box 32

Jirapa, NWR

Ghana

Phone Number: 011 233 20 924 9952

I'm three hours ahead of Atlantic time right now. Feel free to call at any time -- it's nice to hear voices from home. :-)

One last thing -- I've added links to a glossary and to other volunteer blogs. Check them out!

For one, Smith believed that all the religions on earth were correct and not contradictory; all of them were different ways to look at the same problem, in which all religions are united to a common purpose. Ghanaians are very similar in their fusion of beliefs. They incorporate Christian or Muslim beliefs into the traditional tribal beliefs without any problem. Highly educated Ghanaians, some with one or more university degrees in science, believe as readily in ghosts and witchcraft as they do in hydrogen bonding. As far as they’re concerned, nothing in science and religion contradict. Life can be studied or it can be left as it is and shrouded in mysticism. But above all else, it is beautiful. To Ghanaians, everything is Grace.

For one, Smith believed that all the religions on earth were correct and not contradictory; all of them were different ways to look at the same problem, in which all religions are united to a common purpose. Ghanaians are very similar in their fusion of beliefs. They incorporate Christian or Muslim beliefs into the traditional tribal beliefs without any problem. Highly educated Ghanaians, some with one or more university degrees in science, believe as readily in ghosts and witchcraft as they do in hydrogen bonding. As far as they’re concerned, nothing in science and religion contradict. Life can be studied or it can be left as it is and shrouded in mysticism. But above all else, it is beautiful. To Ghanaians, everything is Grace. Maybe we should start flying Ghanaians to

Maybe we should start flying Ghanaians to